Auschwitz: hell and hope

In June, 2005 I visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. I was so moved by what I experienced that day, I wrote the following piece.

On 7 October, 1944 (75 years ago) a special detachment of Jewish prisoner workers who were forced to work in the gas chambers staged an uprising and destroyed one of the crematoria.

The 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau will be commemorated on 27 January, 2020.

********************************************************************************************************

Today I visited the site where the single biggest genocide in the history of mankind took place. Where, at once, the silence speaks of the ferocity and fragility of mankind; of cruelty and courage; of hell and hope. Today, I visited Auschwitz.

Auschwitz (or Oswiecim in Polish) is located 60km west of Krakow, Poland. It was here over the course of five years from 1940 to 1945 that the German Nazis tortured and eventually murdered more than 1.1 million Jewish men, women and children; gypsies; and war prisoners from several European countries.

The size of the camp grew to eventually include Auschwitz II – Birkenau.

Walking through the entrance gates to Auschwitz I, which display the very Nazi sentiment “work brings freedom”, I am aware that I am stepping foot into what is surely one of the most calculated and despicable chapters of modern history. Could the camp’s inmates have ever imagined what lay ahead, as they toiled in vain for their captors, constructing the gas chambers and their own graves?

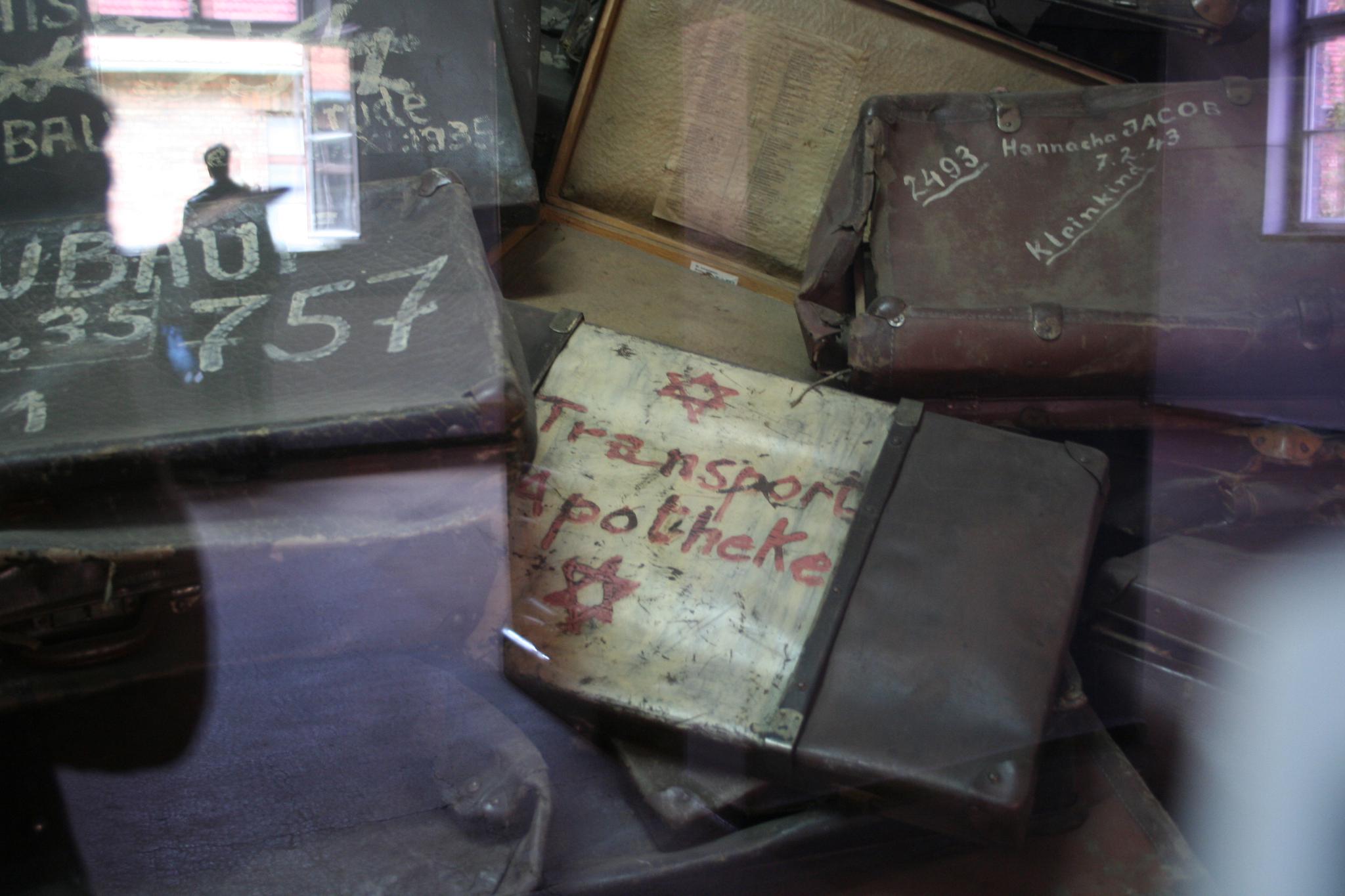

The Nazis wasted nothing. Confronting display rooms in former blocks house huge cabinets, several metres in length and height, with human hair, spectacles, shoes, suitcases and even tooth brushes. All could be reused somehow to enhance the Nazi war effort.

Staring at these ‘human souvenirs’ through tear-filled eyes, I cannot help but mourn the indescribable loss.

Suitcases with the owner’s names and dates of birth written neatly on each one – some with a star of David, some with a child’s scrawl. Luggage that should have been carried by its owners through many roads in life’s travels.

Thousands of shoes – some in infant sizes, others a boy’s boot or a young lady’s red-and-white-striped wedge heel. Shoes which should have ran, skipped, and danced their way through decades of time.

Infant’s clothing – white hand knitted cardigans, booties and bonnets; a child’s floral apron – from children who should have grown to become parents and grandparents. Instead, all these objects now lie covered in dust, lifeless in the world’s biggest cemetery, a poignant reminder of stolen futures and human lives callously ended.

Further blocks contain holding cells where Nazi doctors conducted their hideous and criminal experiments on prisoners, mostly children.

In the passage between two blocks lies the execution square where thousands of Jews were tortured and shot. The two posts still stand where prisoners were tied by their wrists. Today, a memorial stands in the square and flowers, candles, wreaths and stones have all been laid in commemoration. On the day I visit, a group of German schoolchildren are gathered; one reads a prayer before their teacher lays a bouquet of flowers. The awkward shuffling of their footsteps on gravel is the only sound to echo in this miserable enclosure.

Suffocation and torture cells still lie in an underground cellar. Nazi quotes and pictures on the wall reveal their plan to starve the Jewish prisoners to death. Healthy women who weighed 75kg before entering the camp were photographed upon the liberation of Auschwitz, weighing just 25kg. A seemingly old lady, gaunt and worn, is revealed by the picture caption to be just 13 years old. Their emaciated bodies are stripped of clothes, flesh and dignity – their sunken, hollow eyes reveal only small signs of life amid their despair.

At the Birkenau camp, Auschwitz II, three kilometres from Auschwitz I, many of the cells and blocks remain almost completely intact. Brick bunks and cold rotting straw flooring mats was the 'welcoming' rest and shelter for the inmates after a day of extreme forced labour. Of those who did not withstand the days’ work, fellow prisoners were forced to carry home their corpses which were displayed back at camp to other prisoners – just one of the many techniques the Nazis used to engender unspeakable fear. Regular hangings were commonplace. Punishments would include standing barefoot and naked in the snow, doused with cold water. Many prisoners froze to death. The families of anyone who attempted escape were forced to stand outside in the elements for hours or days with a note explaining why they were there – this was to expunge any similar ideas other inmates may have to escape.

At Birkenau, the remains of three crematoria are still standing. One was destroyed by Jewish prisoners in an uprising on 7 October 1944, by the ‘special detachment’ (Sonderkommando) workers who had been forced to burn the bodies of those who were gassed and operate the crematoria. The SS killed all who were involved in the uprising, resulting in 450 murders.

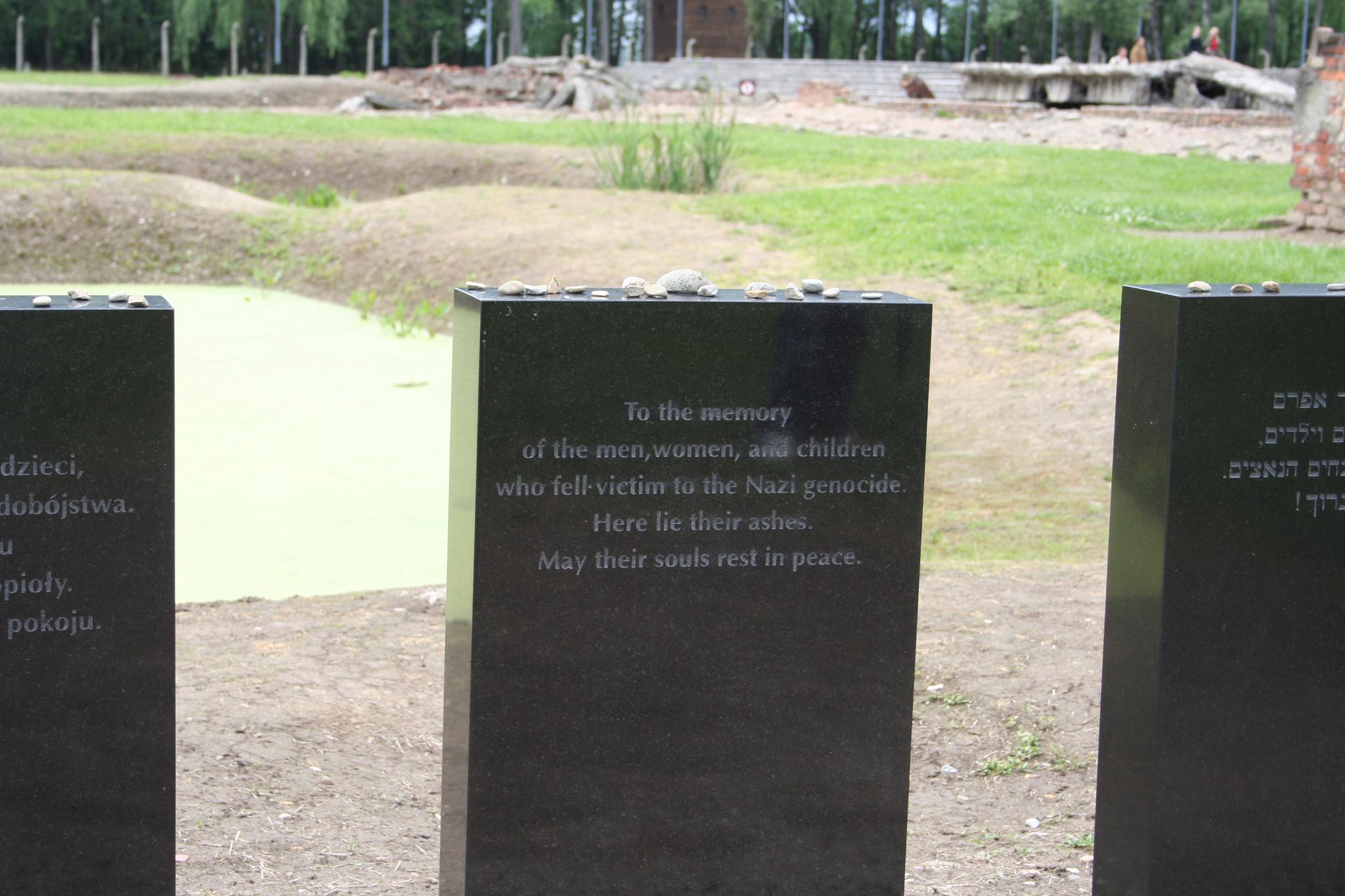

The other two crematoria were destroyed by the fleeing SS troops in an effort to conceal their atrocities. Today, you can still see the steps by which thousands were deceptively led to their deaths in the belief they were taking a shower. The Nazis had false shower heads fitted in the chambers where the only liquid that flowed was a lethal gas. On a busy day at Birkenau, Jews queued in clumps of trees while waiting naively for their ‘shower’.

While the train tracks that led into Birkenau under the Nazi watchtower represented the end of life for millions of people, it was not the end of hope. Decades after its liberation, the journey which all who come here must travel, including the world leaders who visit, is to embrace freedom and fight injustice: to leave here with the resolve that intolerance will never be tolerated; that injustice can never be justified and that ignorance can never be ignored.

Now, at the foot of the rusty barbed wire, flowers grow. In the woods where the hail of bullets once sounded, chirping birds break the silence. Monuments dedicated in English, Hebrew, German, Polish, French and many other languages stand side by side, as do the schoolchildren of Poles and Germans. There can be no greater lesson than history.

Auschwitz is a place I never want to return to and never want to forget.

__________________________________________________________________________

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum is located in the medieval Polish city of Oswiecim, about 66 kilometres west of Krakow.

For more information, visit the official Auschwitz-Birkenau site here.

The 75th anniversary of the liberation of the German Nazi concentration and extermination camp will be commemorated on 27 January 2020. The date of 27 January, the liberation date of Auschwitz, is now the annual International Holocaust Remembrance Day, as declared by the United Nations General Assembly.